sales of 30 – 40 million t by 2014 as

predicted, Mongolia will be lucky to

repeat last year’s volume of

18.3 million t. Coal, the country’s main

revenue earner, contributed just

US$ 1.1 billion in export earnings last

year, down from US$ 1.9 billion in 2012.

In its latest annual assessment issued

in March 2014, the International

Monetary Fund (IMF) blamed the

government for dampening Mongolia’s

once-bright outlook. The fund also

sharply reduced its forecast for the

country’s economic growth over the

next five years, warning that the

country is at “serious risk” of suffering

a balance of payment crisis, due to the

sharp decline in foreign direct

investment.

“External shocks and the

continuation of current policies could

expose vulnerabilities in the banking

system, exacerbating a negative shock

to growth and financial stability,” the

IMF said.

It was just four years ago that the

IMF issued the following glowing

assessment: “Mongolia has a bright

economic future. Its vast mineral

deposits offer the potential to create

strong and sustained growth, lasting

economic prosperity, and a substantial

reduction in poverty.”

The World Bank was just as hopeful

when it upgraded Mongolia’s status

from a poor economy with a GDP per

capita of US$ 528 in 2001 to that of a

lower middle-earner with an income of

US$ 2508 in 2011. Among investment

bankers and traders, there was

widespread talk of the Mongolian

economy growing at rates of 20%/year.

Mongolia’s downfall

Mongolia’s downfall began shortly after

its economy grew by a record 17.5% in

2011. This was Mongolia’s brief golden

moment, as coal prices soared on the

world markets, its exports boomed and

foreign bankers fought each other to

lend money and expertise to Asia’s next

tiger economy.

With so much power and money at

stake, the simmering tensions between

the country’s competing political

factions burst into open fights in 2012,

leading the government to take two

unprecedented actions that have

seriously damaged the country’s

business environment.

In April 2012, Tsakhia Elbegdorj, the

current president, ordered the arrest

and trial of his predecessor and

opposition leader, Nambaryn Enkhbayar.

To no one’s surprise, he was quickly

found guilty of corruption and abuse of

power and sentenced to four years

imprisonment.

Foreign investors barely had time to

react to this political bombshell when

the government intervened to stop

Chinese state-owned aluminium giant,

Chalco, acquiring the majority stake in

one of the country’s major coal mining

firms for US$ 926 million. According to

SouthGobi Resources Ltd, the

Mineral Resources Authority of

Mongolia also suspended its licences to

explore and mine the Ovoot Tolgoi

mine, which holds an estimated

175.7 million t of coal reserves, mostly

for export to China.

The decisions were likely connected,

as Enkhbayar had strong ties with

China and played a key role in opening

up the economy to the foreign

investment that helped launched

Mongolia’s economy. Chinese leaders

frequently praised him for boosting

bilateral ties when he served as

Mongolia’s prime minister between

2000 – 2004, the speaker of the

parliament in 2004 – 2005 and president

from 2005 – 2009.

SouthGobi Resources, which

championed Mongolia as a reliable and

investor-friendly supplier of coal and

other minerals to the world, cited

government security concerns for the

intervention after main shareholder

Ivanhoe Mines (renamed

Tourquoise Hills) announced it wanted

to sell its 57.6% stake to Chalco.

Another Chinese state firm, the

sovereign wealth fund CIC, held a

13.8% stake, potentially giving Beijing a

70.4% controlling ownership in

SouthGobi Resources, if the deal had

been allowed to go through.

The Mongolian Government’s

decision to openly block the sale not

only damaged political and trade ties

with China, its biggest customer and

powerful neighbour, it also scared off

other international investors. Most were

shocked by the speed and force of the

government’s intervention in what was

largely a friendly private takeover of

SouthGobi, a company listed on the

stock exchanges of Toronto and

Hong Kong.

Rather than seek a role for

Mongolian interest to counter Chinese

control of the company, the government

killed off the deal and, in the process,

hurt Canada’s Tourquoise Hills, which

had largely played by the rules in

building up SouthGobi’s value. The

share price of once high-flying

SouthGobi crashed from the agreed sale

price of C$ 8.48/share on 1 April 2012

to around C$ 0.60 in August 2014.

The government ensured there was

no way back for itself when it rushed

through nationalistic legislation in

May 2012 to protect strategic assets

from foreign ownership and control,

effectively telling the world that

Mongolia was no longer open for

business.

The impact of the Strategic Entities

Foreign Investment Law (SEFIL) on the

Mongolian economy was swift and

devastating. After reaching a record

US$ 4.78 billion in 2011, foreign direct

investments (FDI) into the country

slipped to US$ 4.4 billion the following

year before plunging 48% to

US$ 2.29 billion in 2013, according to

the Bank of Mongolia. It is expected to

fall further over the next few years

amid investors’ fears about the

country’s worsening corruption,

bureaucratic interference and rising

political infighting.

The SouthGobi debacle contributed

to investors and international banks

losing interest in the oft-delayed listing

of state-owned Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi

(ETT), which has the licence to develop

and mine large coal deposits in

southern Mongolia. The proposed sale

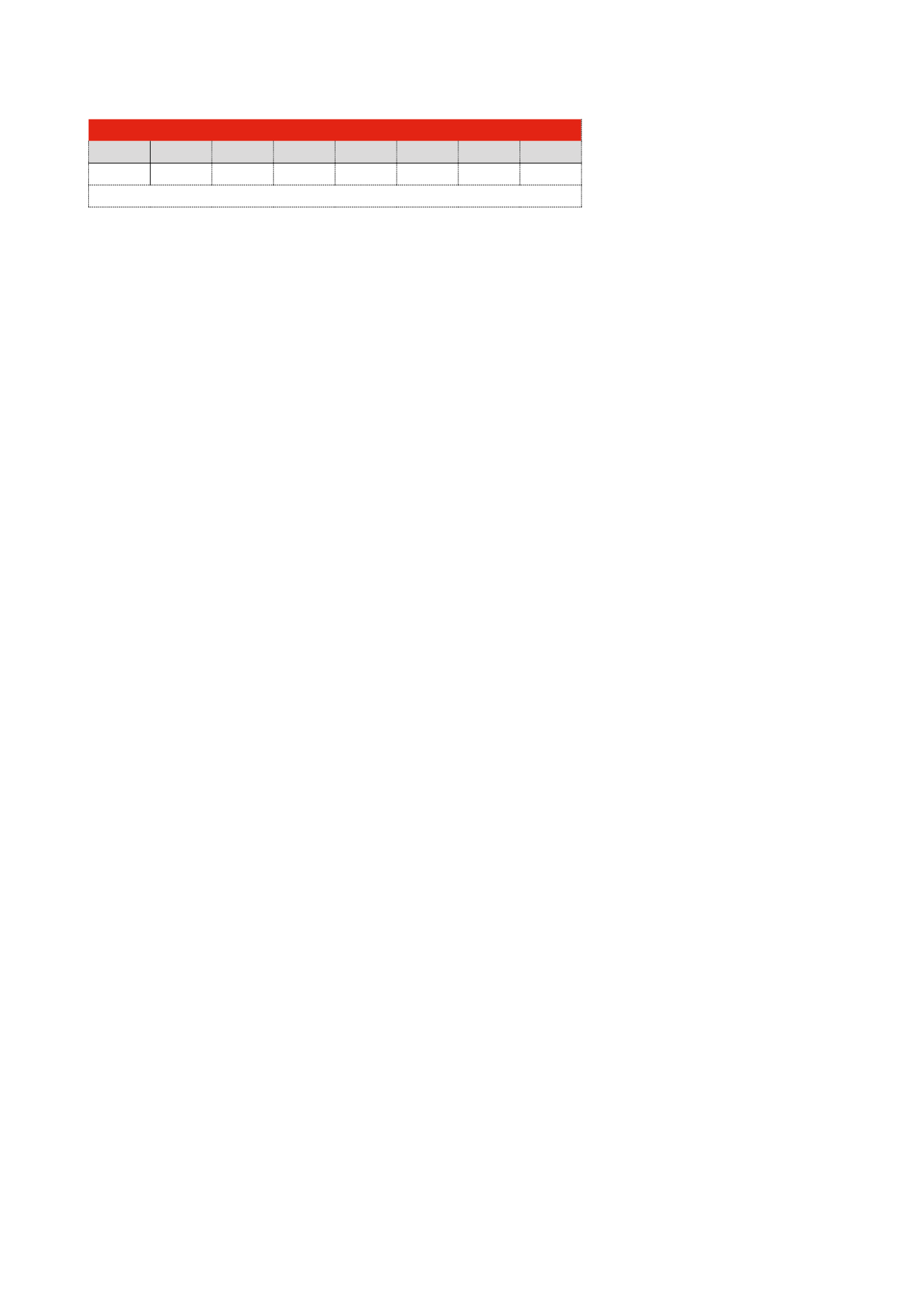

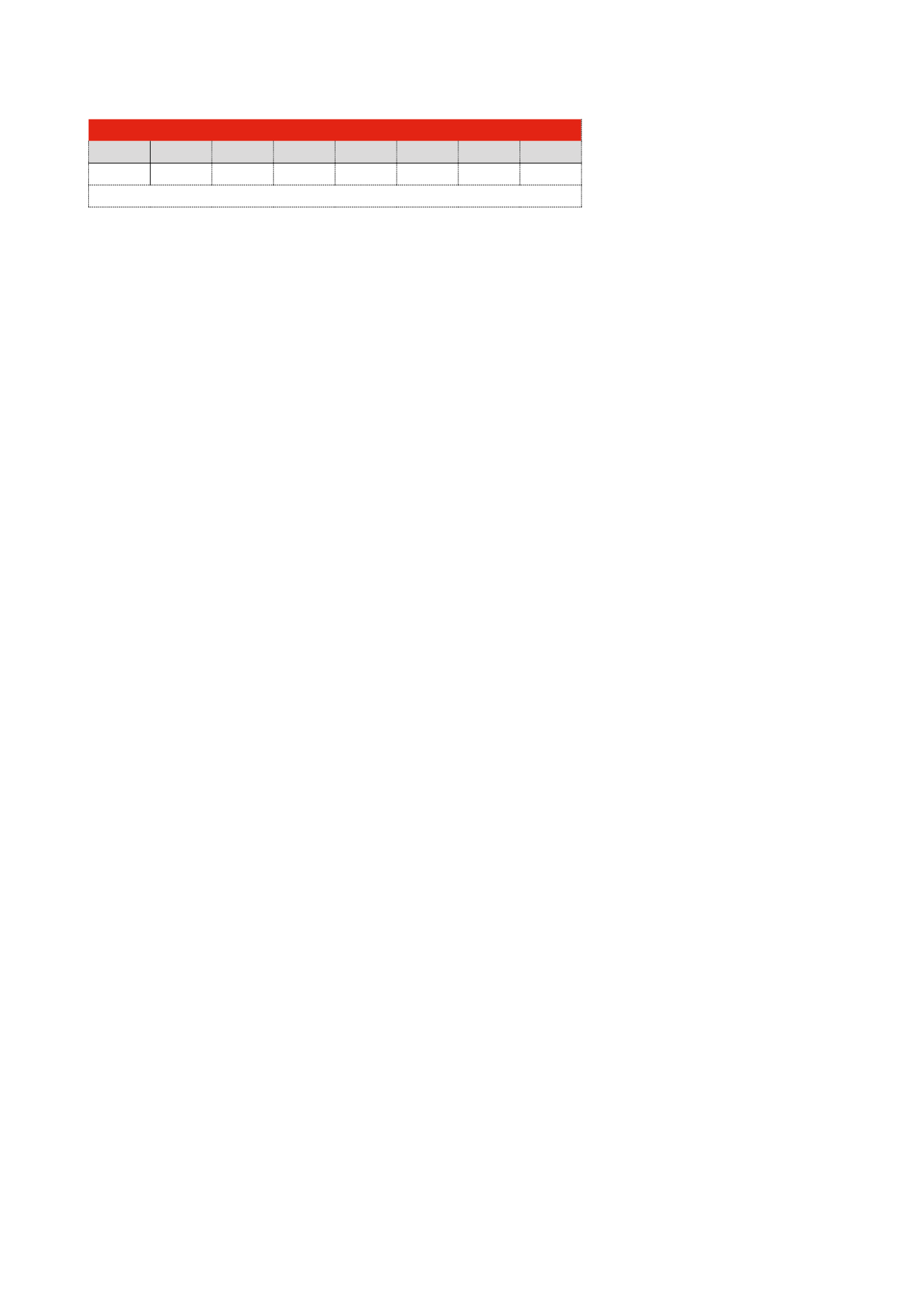

Table 1. Mongolian metallurgical coal exports (million t)

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Coal

3.2

4.2

7.1

16.8

21.1

20.9

18.3

Sources: National Statistics Office of Mongolia, IMF.

14

|

World Coal

|

September 2014